Ergonomics for the Radiologic Technologist

Nov 07, 2025

When you walk into the imaging suite, it’s easy to be drawn to the technology — the hum of the generator, the glow of the console, the precision of the equipment. But beneath the machinery lies an even greater instrument: you.

As a Radiologic Technologist, your body is both a tool and a teacher. Every movement — lifting a patient, positioning a cassette, transferring a stretcher — becomes an act of biomechanics. Mastering ergonomics isn’t about comfort alone; it’s about longevity, safety, and precision. It’s how you preserve your body so that you can preserve the health of others.

Ergonomics, as defined in your training, is the study of the human body in relation to its working environment. Its goal is clear and urgent: to prevent injury. The U.S. Department of Labor estimates that musculoskeletal injuries — particularly sprains and strains — are the leading cause of disability among healthcare workers. Each year, over 600,000 medical professionals suffer from preventable injuries caused by poor movement, improper lifting, and fatigue.

Yet, through the principles of body mechanics, radiographers can transform vulnerability into strength.

The Foundation: Body Mechanics as the Science of Movement

At its core, body mechanics is the application of physics to the human body — principles of alignment, balance, and movement that allow us to work efficiently while minimizing strain. It’s not merely about moving patients; it’s about understanding how you move in relation to them.

In radiography, this knowledge becomes a form of self-protection. Each transfer, pivot, or reach carries risk if not executed with awareness. Proper body mechanics turn the potential for harm into an opportunity for mastery.

Three foundational concepts form the language of ergonomics: base of support, center of gravity, and line of gravity.

Base of Support: Stability Before Motion

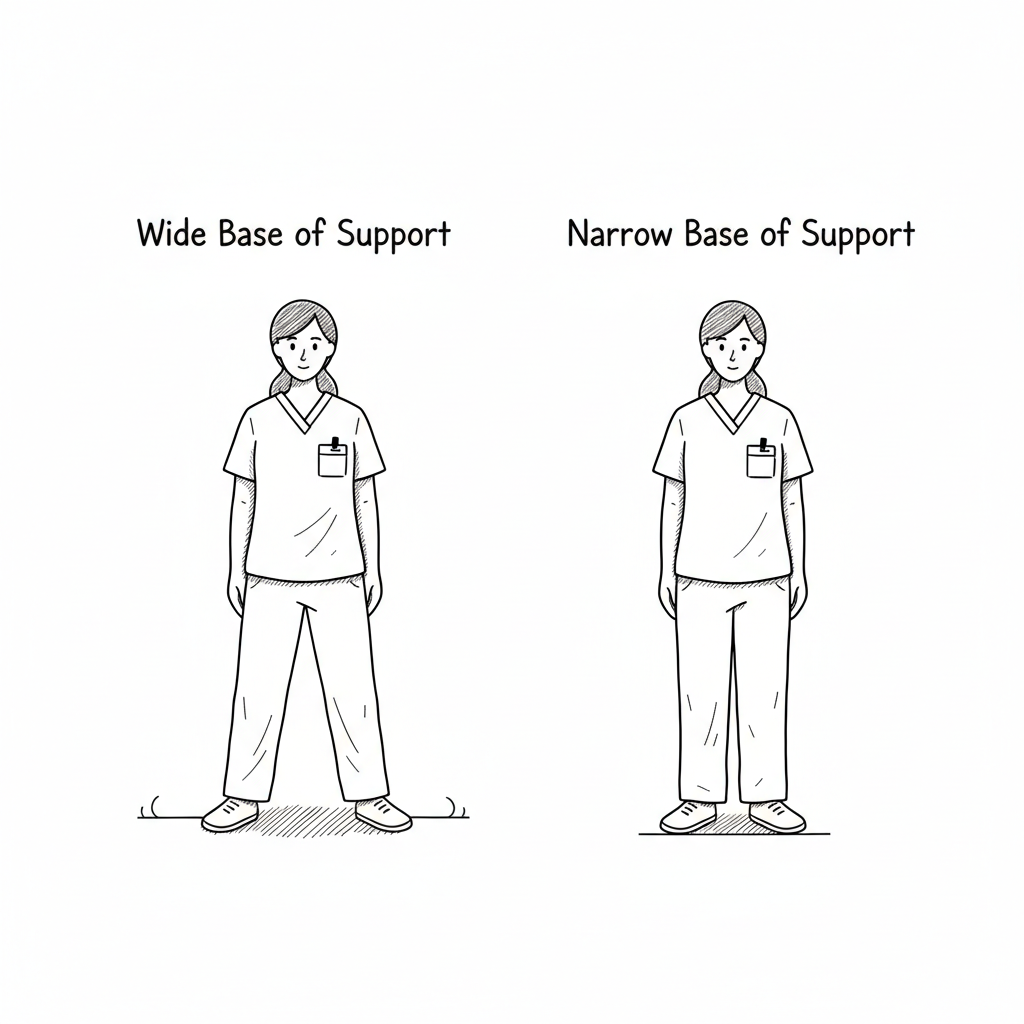

Your base of support is the foundation on which your body rests — the contact points between you and the ground. In practice, it’s your stance. A wide base — feet shoulder-width apart, one foot slightly forward — provides stability and control. A narrow base, by contrast, creates instability and increases the risk of falls or imbalance.

When transferring a patient or manipulating equipment, widen your stance and ground yourself before you act. The wider your base, the more stable your body — and the safer your patient.

[Insert Diagram: Illustration showing “Wide vs. Narrow Base of Support” — feet placement demonstrating increased stability.]

Center of Gravity: The Balance of Strength

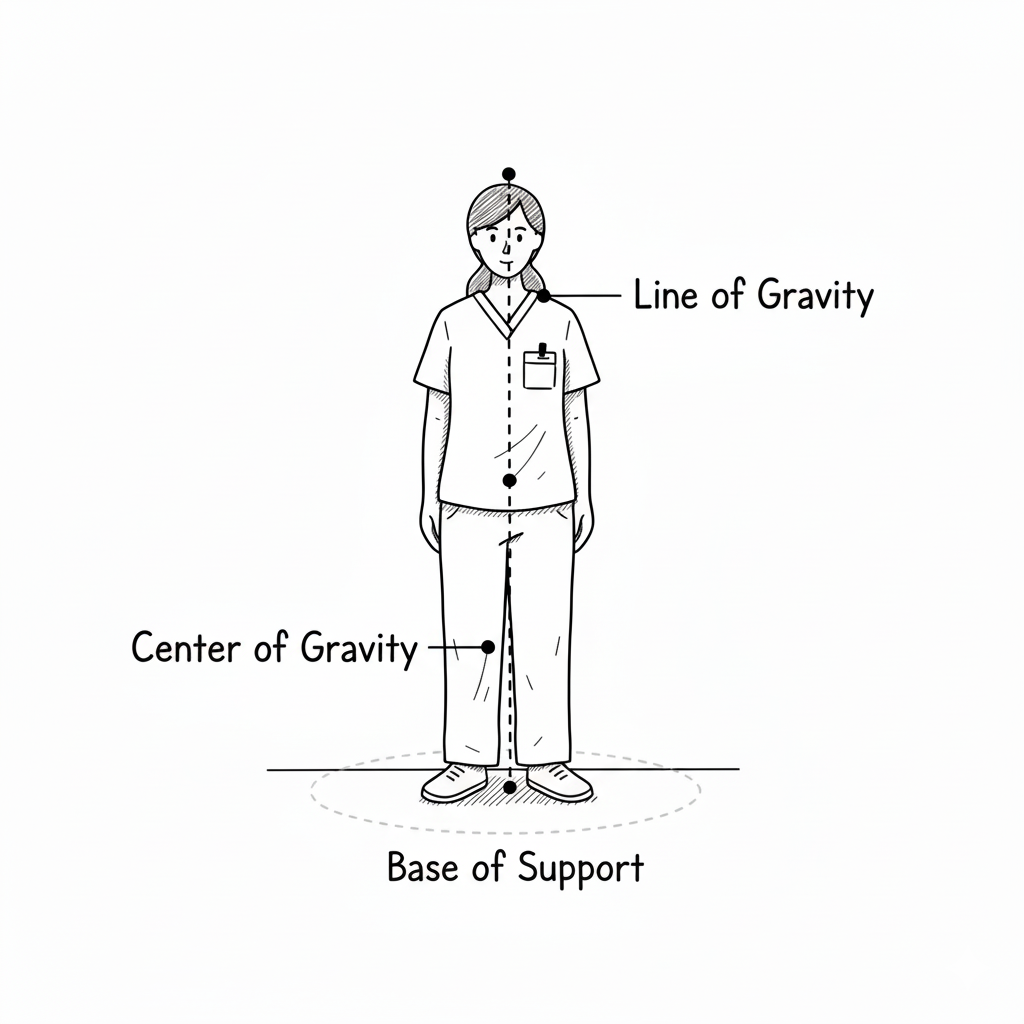

The center of gravity (COG) is the point where the body’s weight is perfectly balanced. In the human body, it lies near the mid-pelvis or lower abdomen (around the level of the second sacral vertebra). When you lift or carry a load, such as supporting a patient’s torso or moving equipment, the safest approach is to keep the weight close to your own center of gravity.

Every inch a load moves away from your core, its strain multiplies. Bringing it close reduces leverage forces and preserves spinal integrity. When your COG aligns directly above your base of support, you achieve equilibrium — strength without strain.

Line of Gravity: The Invisible Axis of Control

Imagine an invisible vertical line passing through your center of gravity and down through the floor — this is your line of gravity. Your body is most stable when this line bisects your base of support. If it shifts beyond your base (as when leaning too far forward or backward), your balance is compromised.

In radiography, the line of gravity matters when reaching for overhead equipment, positioning patients on a stretcher, or stepping onto a mobile platform. By keeping your line of gravity centered, you convert instability into control.

Rules of Body Mechanics: The Five Pillars of Protection

Radiography is a profession of repetition — bending, pushing, transferring, and reaching hundreds of times each day. Over time, these movements shape not only your posture but your career.

To preserve both, apply these five rules of body mechanics:

-

Establish a broad base of support. Stand with feet apart, one slightly forward.

-

Work at a comfortable height. Adjust tables, beds, or equipment to match your reach — not the other way around.

-

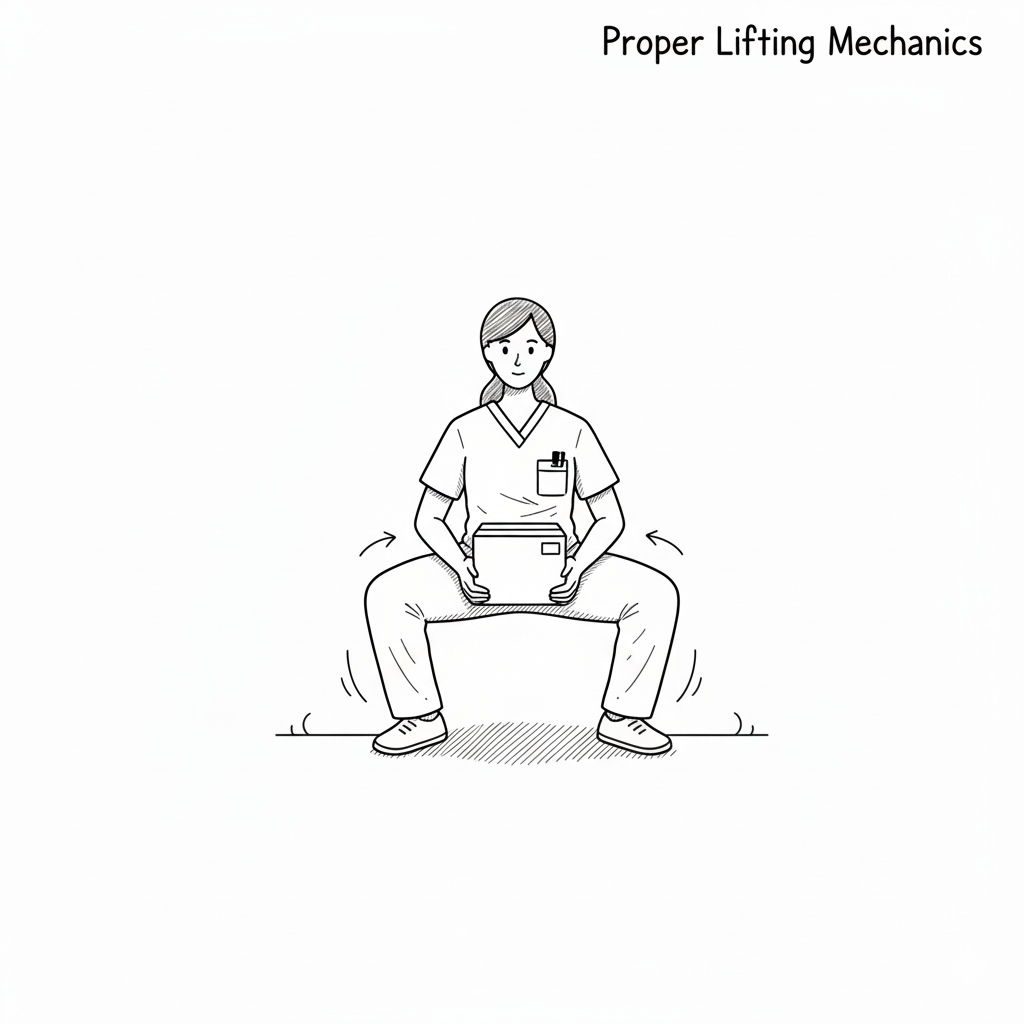

Bend with your knees, not your back. Let the power of your legs, arms, and abdomen carry the load.

-

Keep your load close. Distance multiplies force; proximity preserves control.

-

Push rather than pull. Whenever possible, use the stronger muscle groups of your legs to move heavy objects or patients.

These principles are deceptively simple — but like exposure settings, they must become instinct. You don’t think about them; you live them.

Biomechanics: Where Physics Meets Compassion

The most skilled technologists are not those who simply endure the work, but those who perform it elegantly — aware that every movement expresses both strength and care. Biomechanics is not a dry branch of physics; it is the study of grace under pressure.

When you move correctly, you move with purpose. You protect yourself so you can protect others. You align your body with the physics of safety — transforming motion into mindfulness.

In the next section, we’ll examine how these principles translate into real-world radiographic practice — exploring patient transfer techniques and the use of safe handling devices that embody the science of ergonomics in motion.

Patient Transfer Techniques: The Art of Safe Motion

Radiologic Technologists perform hundreds of patient transfers over the course of a career — from stretchers to tables, from wheelchairs to imaging beds, from standing to seated. These repetitive movements, when performed incorrectly, can cause chronic injuries that end careers prematurely. But when performed correctly, they become a seamless choreography between strength, awareness, and empathy.

Safe patient transfer is not simply about moving bodies; it is about maintaining dignity, safety, and control for both patient and technologist. Proper technique is the embodiment of ergonomic intelligence — physics applied with compassion.

Preparing the Environment

Before any transfer, the technologist must prepare the environment. Most injuries occur not from lifting but from haste. Slow down, assess, and plan.

-

Clear all obstacles. Ensure that tubes, lines, footrests, and equipment are out of the way.

-

Adjust bed or table height. Align it to just below the patient’s waistline — the level where your body exerts maximum control.

-

Lock wheels. Both the wheelchair and the stretcher must remain stationary.

-

Explain the process. Tell the patient exactly what will happen, step by step. A calm, informed patient assists in their own safety.

Every transfer begins not with movement but with communication.

The Basic Principles of Safe Transfer

-

Establish your stance.

Position your feet shoulder-width apart with one foot slightly forward — your broad base of support. -

Face the direction of movement.

Avoid twisting your spine. Pivot with your feet, keeping your shoulders and hips aligned. -

Engage your core.

Tighten abdominal muscles to support your spine and maintain stability. -

Lift with your legs, not your back.

The quadriceps and gluteal muscles are powerful; use them. Your lower back is not designed to bear heavy loads. -

Maintain close contact.

Keep the patient as close to your body as possible. The closer the load, the safer the lift.

Types of Transfers in Radiography

Wheelchair to X-ray Table Transfer

-

Move the wheelchair at a 45-degree angle to the table.

-

Lock the wheels and move the footrests aside.

-

Assist the patient to the edge of the wheelchair seat.

-

Place your arms around the patient’s torso or under the arms, depending on their ability.

-

Use a pivot motion, turning your whole body as one unit to guide the patient onto the table.

Encourage the patient to assist when possible — by pushing off the armrest or footrest. This shared effort minimizes risk for both parties.

Stretcher to Table Transfer

This transfer is common in trauma, surgery, and fluoroscopy suites. Here, teamwork and equipment are vital.

-

Ensure that both surfaces are level and locked in position.

-

Use a draw sheet, slide board, or transfer board to minimize friction.

-

Assign roles among staff: one person stabilizes the head and neck, one coordinates the lift, and others assist at the torso and legs.

-

On command, slide — don’t lift — the patient across the board using slow, synchronized movement.

Never attempt to lift a patient independently when mechanical aids or help are required. Injuries occur not from weakness, but from pride.

[Insert Diagram: Transfer Board in Use — Patient moving horizontally between stretcher and table.]

Standing Transfer

Used for ambulatory patients who can bear partial weight.

-

Have the patient scoot to the edge of the chair or table.

-

Position your feet outside theirs to provide stability.

-

Ask the patient to place their hands on your forearms or on the wheelchair arms — not around your neck.

-

On count of three, rise together using leg strength.

-

Pivot as one unit toward the table, maintaining alignment and balance.

Every successful standing transfer reflects mutual trust. The patient must feel your steadiness before they commit their weight to your guidance.

Safe Patient Handling Devices: Technology as an Extension of Care

Modern radiography embraces not only ergonomic technique but also ergonomic technology. Safe patient handling devices protect both patients and healthcare workers, embodying the principle that good mechanics should be supported by good design.

Transfer Boards (Slide Boards)

A transfer board is a smooth, rigid surface placed beneath the patient to bridge two horizontal surfaces — such as a stretcher and a radiographic table. The board reduces friction, allowing the patient to glide rather than be lifted.

This device is especially useful for trauma, bariatric, or immobile patients. It conserves energy, prevents skin shear, and drastically reduces back strain on staff.

Gait Belts

A gait belt is a sturdy fabric belt secured around the patient’s waist, providing a safe handhold during standing or walking transfers. It gives the technologist control without resorting to risky or invasive grips.

When applying a gait belt, ensure it’s snug but comfortable. Grasp the belt from underneath, never pulling upward. This approach allows you to guide rather than lift, stabilizing both you and the patient during ambulation.

Hoyer Lifts (Mechanical Lifts)

For patients who are unable to assist, the Hoyer lift — a mechanical lifting device — provides full-body support. Using a sling and hydraulic or electric mechanism, it raises and transfers patients safely between beds, wheelchairs, and imaging tables.

Using a Hoyer lift may feel impersonal at first, but it is an act of profound care. It protects the patient from falls and preserves the technologist’s physical integrity. True professionalism lies not in physical strength, but in the wisdom to use the tools of safety.

The Human Element in Mechanical Motion

Technology cannot replace the human touch — but it can amplify it. When you combine empathy with technique, and technology with awareness, you embody the highest form of ergonomic practice. Every safe transfer is a partnership between physics, equipment, and compassion.

Posture Awareness: The Unseen Discipline

Ergonomics doesn’t end once the patient is positioned. It extends into every quiet moment between exposures — how you stand, sit, and move throughout your shift. Over time, small postural errors compound like radiation exposure, accumulating unseen damage until the body protests.

Poor posture is one of the most overlooked hazards in radiography. Leaning over consoles, reaching across tables, twisting to align a patient — each micro-movement, if repeated incorrectly, shapes muscle memory that can lead to chronic pain.

A neutral posture keeps the spine in its natural “S” curve, distributing weight evenly. Shoulders relaxed, chin slightly tucked, knees soft, abdominal muscles gently engaged — this stance creates an invisible armor against fatigue. When working at a console or computer, the monitor should be at eye level, wrists straight, and elbows at a 90-degree angle.

Your body tells stories long before your words do. Patients notice when you move with composure. They interpret it as confidence — and confidence breeds trust.

Microbreaks and Movement: The Antidote to Fatigue

Fatigue is the silent thief of precision. The longer your shift, the heavier your body feels and the more likely your form deteriorates. The solution lies in microbreaks — brief, intentional pauses that restore circulation and awareness.

Every 30–45 minutes, step away from the console or imaging bay. Stretch your shoulders backward, roll your neck gently, or flex your calves and ankles. Take slow, measured breaths to reoxygenate the body and refocus the mind. Even 60 seconds of mindful movement can reset posture and prevent repetitive strain injuries.

Ergonomics isn’t about rigid stillness — it’s about balance in motion. The human body is designed to move. When we deny it motion, we invite dysfunction.

Some technologists practice a simple mantra: “Reset before regret.” Before every transfer, every procedure, or every long stretch at the workstation — reset your stance, your breath, and your awareness.

Preventing Burnout: Ergonomics for the Mind

While ergonomics is rooted in physical science, its ultimate goal is holistic wellness — the integration of body, mind, and purpose. A technologist cannot serve with excellence if exhaustion becomes their baseline.

Burnout in radiography often begins not with overwork but with overexertion without recovery. It starts when we ignore small signals — a sore back, an aching wrist, a stiff neck — until those signals become alarms. The same awareness that protects your spine also protects your spirit.

Three habits guard against ergonomic burnout:

-

Mindful Presence:

Before lifting or positioning, pause. Breathe. Let each motion be deliberate, not rushed. This not only improves safety but cultivates inner calm. -

Collaborative Teamwork:

Ask for assistance without hesitation. Pride is the enemy of longevity. True professionals know that teamwork is strength, not weakness. -

Continuous Learning:

Ergonomics evolves with technology. Each new modality — from digital tomosynthesis to mobile C-arm fluoroscopy — presents new mechanical challenges. Stay current with best practices, in-service training, and institutional ergonomics policies.

As one ergonomics text notes, “The technologist who neglects their own body becomes their first injured patient.” Caring for yourself is not self-indulgence; it’s ethical responsibility.

Ergonomics as Professional Identity

In radiography, precision is everything. A millimeter off in alignment can distort an image; a misaligned spine can distort a career. The disciplined technologist understands that ergonomics is not an accessory to professionalism — it is professionalism.

Every movement communicates competence. When you adjust a stretcher smoothly, when you transfer a patient without strain, when you reach for the tube head with centered balance — you are teaching by example. Students, patients, and peers watch and learn what care looks like.

True mastery of ergonomics transforms the workplace into an extension of your anatomy. Equipment becomes fluid in your hands. Space feels calibrated to your rhythm. Fatigue gives way to flow — that state where work feels effortless because every motion is aligned with natural mechanics.

This harmony between body and environment is the essence of ergonomic excellence. It’s how a career endures not just physically, but meaningfully.

A Final Reflection: The Grace of Movement

When you first enter x-ray school, ergonomics can feel like an afterthought — a checklist of lifting rules and posture tips. But as your training deepens, you begin to see it differently. You realize that ergonomics is the discipline that lets your vocation last.

It’s what ensures that decades from now, you can still do what you love without pain or limitation. It’s what lets you bend over a trauma patient at 2 a.m. and lift with confidence. It’s what lets you end a 12-hour shift tired but unbroken — body intact, mind clear, purpose intact.

Ergonomics, at its core, is not about preventing injury. It’s about preserving passion.

The radiologic technologist who moves with awareness moves with grace. Their posture becomes their philosophy — strong yet flexible, grounded yet compassionate.

In a profession defined by images, ergonomics shapes the one image that matters most: you — the technologist who embodies both precision and presence, science and care, power and humility.

That’s the physics of care. That’s ergonomics — not as a concept, but as a way of being.

Stay connected with news and updates!

Join our mailing list to receive the latest tips, tricks and insights to help you pass your registry!

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.