Infection Control Part 1: The Cycle of Infection

Nov 10, 2025

Step into any imaging department, and you’ll find precision everywhere — calibrated machines, sterile instruments, and protocols etched into daily routine. But beneath that precision flows an invisible reality: the constant motion of microorganisms. Some harmless. Some vital. And some — if left unchecked — capable of crippling a patient’s recovery or derailing a technologist’s career.

For students of radiologic technology, mastering infection control isn’t just about passing the ARRT® exam; it’s about embodying the mindset of vigilance that defines the profession. In radiography, where direct patient contact and invasive procedures are common, understanding the cycle of infection transforms knowledge into protection — for both the patient and the technologist.

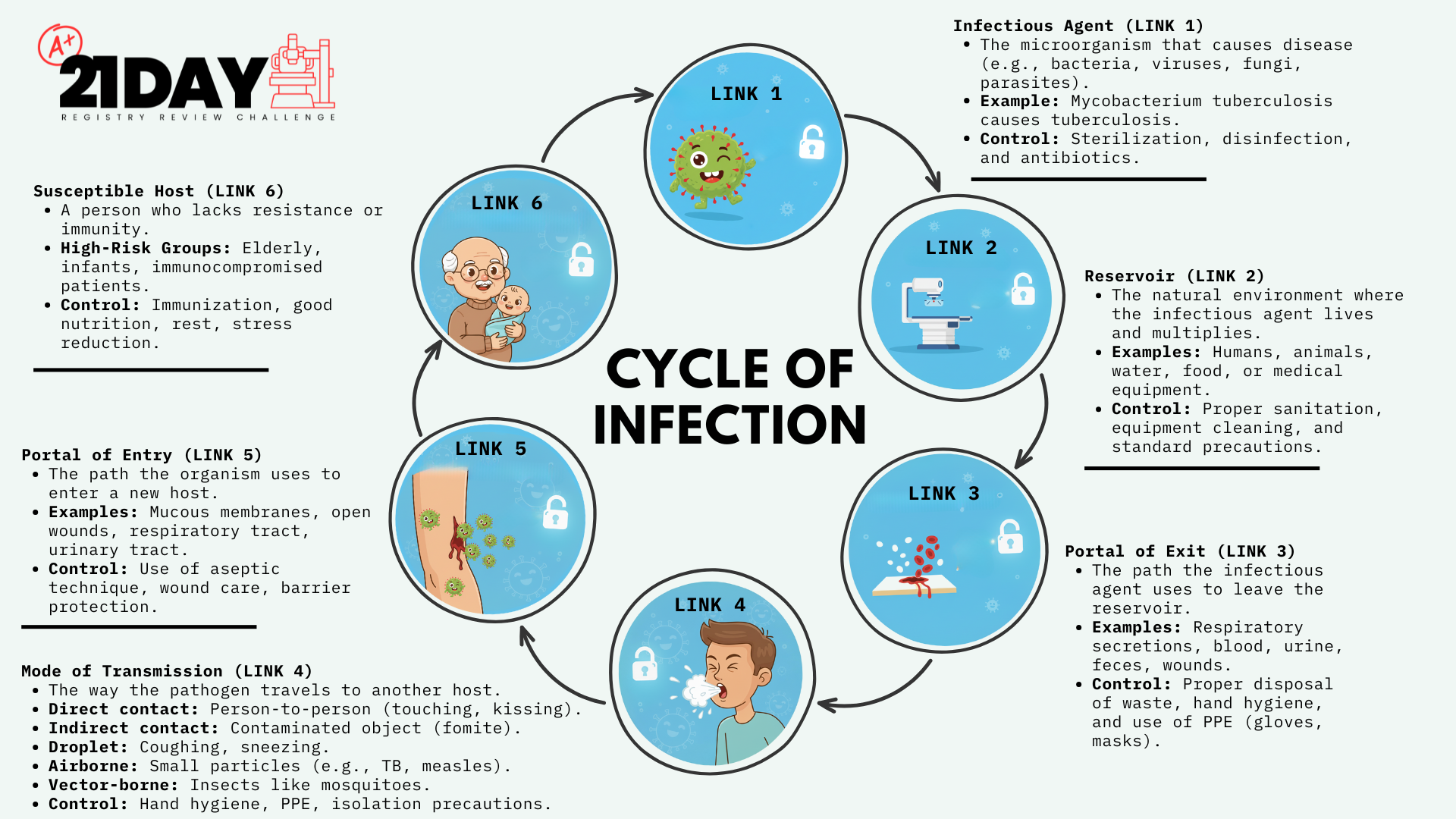

1. The Cycle of Infection: The Hidden Chain Behind Every Disease

The cycle of infection explains how disease spreads — step by step — from its source to a new host. It has six essential links, and when any one of these links is broken, infection can be stopped in its tracks. This is the foundation upon which all infection control principles are built.

The six links are:

-

Pathogen (infectious agent)

-

Reservoir

-

Portal of exit

-

Mode of transmission

-

Portal of entry

-

Susceptible host

Each link is a potential point of intervention — a place where the technologist’s awareness and action can halt infection’s progress.

Let’s move through each link, examining its meaning and its direct application to radiologic practice.

2. Pathogen: The Invader

Every infection begins with a pathogen — a microorganism capable of causing disease. Not all microorganisms are dangerous. In fact, many are essential to human health, forming the body’s normal flora — protective bacteria that help digest food and keep harmful microbes in check. But pathogens are different. They are the microscopic invaders that destroy tissue, release toxins, and exploit weakness.

A pathogen’s ability to cause disease depends on two key factors:

-

Pathogenicity – its ability to cause disease.

-

Virulence – the degree of severity with which it does so.

Some pathogens are highly virulent, like Mycobacterium tuberculosis, capable of thriving in airborne droplets. Others, like Staphylococcus aureus, lurk harmlessly on skin until an opportunity — such as a cut or puncture — grants access to deeper tissue.

For radiographers, the front line of defense is asepsis — the practice of maintaining an environment free from disease-producing organisms. Whether cleaning equipment, wearing gloves, or avoiding cross-contamination, your role is to ensure pathogens have no chance to complete their cycle.

3. Reservoir: The Pathogen’s Home Base

Pathogens need a place to live, grow, and multiply before they can spread. This is known as the reservoir of infection. The human body — warm, moist, and nutrient-rich — is an ideal environment. But reservoirs aren’t limited to people; they can include animals, food, water, and even soil.

In the clinical setting, reservoirs can be as ordinary as a contaminated positioning sponge, a used lead apron, or the human hand that forgets to wash between patients.

To thrive, pathogens require:

-

Moisture

-

Nutrients

-

A suitable temperature

In radiography, preventing reservoirs is an active duty. Keep food and drinks out of patient areas. Disinfect equipment between exams. Avoid touching your face, phone, or personal items after patient contact. Even small lapses — a pen handled with gloved hands or an uncleaned tabletop — can sustain the invisible ecosystem of infection.

Remember: the most dangerous reservoirs are the ones you never notice.

4. Portal of Exit: The Pathway Out

Once established in a reservoir, pathogens must find a portal of exit — a way to escape and continue their cycle. In humans, these exits are the body’s natural openings and wounds:

-

The respiratory tract (through coughing, sneezing, or talking)

-

The gastrointestinal tract (via feces or vomit)

-

The urinary tract

-

Open wounds, cuts, or abrasions

-

Blood and other bodily fluids

In radiologic environments, portals of exit are especially relevant during fluoroscopy, mobile imaging, and trauma cases where body fluids are exposed. When a technologist handles contaminated dressings, bed linens, or bodily waste without proper protection, they become part of the transmission pathway.

Breaking this link means containing what leaves the patient — wearing gloves, masks, and gowns as appropriate, and disposing of contaminated materials according to protocol. Even an uncovered wound or an unmasked cough can extend the chain of infection.

A patient coughing in a chest x-ray room isn’t just a nuisance — it’s a lesson in epidemiology unfolding before your eyes.

5. Mode of Transmission: The Path the Pathogen Travels

Once a pathogen escapes its reservoir, it must find a route to reach a new host. This route is known as the mode of transmission, and in radiologic technology, it represents the link most often broken through intentional, consistent control measures.

There are two primary categories of transmission: direct and indirect.

Direct Transmission: Person-to-Person Contact

In direct transmission, microorganisms pass from one person to another without an intermediary. It happens when infectious material touches skin, mucous membranes, or open wounds.

There are two common types of direct transmission in healthcare:

-

Droplet Transmission

-

Occurs when infectious droplets (usually larger than 5 micrometers) are expelled by coughing, sneezing, or even speaking, and make contact with the mucous membranes of another person’s mouth, nose, or eyes.

-

Examples include influenza, meningitis, diphtheria, and pertussis (whooping cough).

In radiography, droplet transmission can occur during close patient interaction — such as positioning for chest x-rays or fluoroscopy — particularly when the patient is coughing or talking. Surgical masks and protective eye shields are vital when working within three feet of a symptomatic patient.

-

-

Direct Contact Transmission

-

Involves the physical transfer of microorganisms between an infected or colonized person and a susceptible one.

-

This can happen when a technologist handles contaminated skin, dressings, or wounds without proper gloves — or when gloved hands touch multiple surfaces before removal.

A handshake, a lifted arm during positioning, or the simple act of stabilizing a patient’s shoulder can all become vectors if precautions lapse.

-

Breaking this chain means strict adherence to hand hygiene — before and after patient contact, even when gloves are worn. It also means maintaining the discipline of single-patient use: one glove set, one disinfectant wipe, one procedure.

Indirect Transmission: When the Pathogen Finds a Middleman

In indirect transmission, microorganisms travel via another object or medium — a silent courier carrying infection from one host to another.

Indirect transmission can occur in three forms:

-

Airborne Transmission

-

Pathogens travel on microscopic particles that remain suspended in the air for long periods.

-

Diseases like tuberculosis, varicella (chickenpox), and measles spread this way.

-

Airborne precautions require negative-pressure rooms, N95 respirators, and limited room access.

For radiographers, this means that portable exams on airborne isolation patients must follow strict infection control: keeping the door closed, donning N95 masks before entry, and disinfecting equipment immediately after use.

-

-

Vehicle-Borne (Fomite) Transmission

-

Occurs when pathogens transfer via contaminated objects — known as fomites.

-

Examples include radiographic tables, positioning sponges, control panels, and even pens or phones.

Every object in a radiology suite can become a potential carrier. The digital era has replaced cassettes with detectors, but not the need for disinfection. Wipe all surfaces between patients. Never place clean equipment on potentially contaminated surfaces.

-

-

Vector-Borne Transmission

-

Involves insects or animals (vectors) transmitting infection to humans — for example, mosquitoes carrying malaria or ticks spreading Lyme disease.

-

Though rare in hospital radiography, it underscores the need for environmental control in mobile or field imaging.

-

Indirect transmission thrives on neglect. It’s not the patient’s cough or wound that spreads disease — it’s the unwashed detector, the shared keyboard, the forgotten wipe.

6. Portal of Entry: The Pathway In

For infection to occur, pathogens must gain access to the host — the portal of entry. This is the mirror image of the portal of exit, often using the same bodily routes.

Common portals of entry include:

-

Respiratory tract – inhalation of droplets or airborne particles.

-

Gastrointestinal tract – ingestion of contaminated food or water.

-

Mucous membranes – eyes, nose, and mouth.

-

Breaks in skin – from cuts, abrasions, punctures, or even small skin cracks.

-

Invasive devices – such as catheters, IV lines, or surgical wounds.

In radiologic practice, the portal of entry is where vigilance must become second nature. Every time you reposition a patient with a line, tape, or drain, you’re one move away from introducing pathogens into the body.

Avoid touching open wounds. Do not adjust catheters or tubing without permission from the nurse or physician. Always wear gloves when contact with bodily fluids is possible. Clean your hands before gloving and after removal.

These actions are not just tasks; they’re a ritual — one that affirms your respect for the invisible barrier between safety and contamination.

When performed with mindfulness, they turn routine into reverence — the daily art of protecting the people who trust you most.

7. The Susceptible Host: When the Body’s Defenses Fall

The final link in the cycle of infection — the susceptible host — is the most personal, the most human. It’s the point where biology meets circumstance, where vulnerability decides whether exposure becomes illness.

A susceptible host is any person who lacks the defense mechanisms to resist infection after exposure to a pathogen. Immunity can be compromised by age, disease, medical treatments, or stress. In radiologic technology, recognizing and respecting susceptibility isn’t just about medical understanding — it’s about empathy in action.

Certain patients are more vulnerable than others:

-

Elderly patients, whose immune systems naturally weaken with age.

-

Infants and children, who have underdeveloped immune responses.

-

Patients with chronic diseases, such as diabetes, cancer, or autoimmune disorders.

-

Postoperative and trauma patients, whose skin barriers have been breached.

-

Immunosuppressed individuals, including those receiving chemotherapy, organ transplants, or corticosteroid therapy.

Even stress and fatigue — in both patients and technologists — lower immune resistance, allowing opportunistic pathogens to thrive.

Understanding susceptibility changes how we practice. The technologist who rushes through positioning, who neglects to wipe down a detector, who forgets to change gloves between patients — unintentionally becomes the vector in someone else’s story. But the technologist who slows down, who disinfects deliberately, who anticipates vulnerability — that technologist breaks the chain of infection before it ever closes.

8. The Cycle Reimagined: Breaking the Links in Radiologic Practice

To visualize the cycle of infection is to see it as a perfect circle — continuous and unrelenting unless interrupted. But for the Radiologic Technologist, every moment in patient care is an opportunity to break one of its links.

Let’s revisit each link and identify your point of influence:

-

Pathogen:

-

Practice medical and surgical asepsis.

-

Clean and disinfect equipment between patients.

-

Use sterile technique when required for invasive procedures (such as myelography or angiography).

-

-

Reservoir:

-

Eliminate moisture and organic debris on surfaces.

-

Store linens and sponges properly.

-

Avoid eating or drinking in clinical areas.

-

-

Portal of Exit:

-

Cover wounds or drainage sites.

-

Handle bodily fluids and waste with gloves and proper disposal containers.

-

-

Mode of Transmission:

-

Wash hands before and after patient contact.

-

Follow transmission-based precautions (airborne, droplet, contact).

-

Clean detectors, tables, and immobilization devices consistently.

-

-

Portal of Entry:

-

Protect your own skin with gloves and avoid open lesions.

-

Use masks, eye protection, and gowns when exposure is possible.

-

Keep invasive devices sterile and undisturbed.

-

-

Susceptible Host:

-

Recognize patient risk factors.

-

Maintain immunization compliance and your own health.

-

Provide education and reassurance to anxious or immunocompromised patients.

-

Infection control is not a checklist — it’s a mindset. The more you internalize these principles, the more naturally you act in ways that protect.

9. The Professional Ethic of Prevention

In radiography, infection control reflects the profession’s deepest value: do no harm.

It’s a principle that transcends procedure — it’s visible in how you wipe a table, how you tie your gown, how you pause to wash your hands even when no one is watching.

For the radiologic technologist, infection control is an ethical discipline. It speaks to the integrity of your craft — to the trust patients place in you when they can’t protect themselves.

When you break one link in the chain, you’re not just stopping an infection; you’re honoring that trust. You’re transforming routine into reverence — the quiet kind of excellence that defines a true professional.

10. Infection Control and the ARRT® Mindset

Students studying for the ARRT® exam often approach infection control as a set of definitions to memorize: pathogen, reservoir, portal of exit, transmission, portal of entry, susceptible host. But the exam — and your career — demand something deeper: understanding how these concepts interconnect in real time.

When you stand in a fluoroscopy suite assisting a contrast study, you’re not simply performing steps; you’re managing every link in the cycle of infection. The gloves, the mask, the table prep — they all exist to break that chain.

The ARRT® tests knowledge, but radiography itself tests character. Infection control requires self-discipline when no one is watching, consistency when you’re tired, and compassion when a vulnerable patient depends entirely on your vigilance.

This is where technical skill meets moral responsibility.

11. Closing Reflection: The Invisible Art of Clean Work

In the end, infection control isn’t about sterility for sterility’s sake. It’s about stewardship — caring for patients and colleagues by creating a space where safety is invisible but absolute.

The cycle of infection is ancient, relentless, and indifferent. But within it stands the Radiologic Technologist — a guardian of the unseen, a breaker of chains. Each hand wash, each disinfectant wipe, each pair of gloves donned with intention is a quiet act of protection.

The world will never see the infections you prevent. There are no plaques or certificates for the diseases that never occurred because you were vigilant. Yet that unseen impact — that ripple of safety — defines your legacy far more than any image ever will.

So when you scrub, wipe, and sanitize, remember: you are not just cleaning equipment — you are breaking the oldest chain in medicine. You are embodying the highest ethic of radiography: precision, protection, and care.

That’s the art of infection control. That’s the unseen image that endures.

Stay connected with news and updates!

Join our mailing list to receive the latest tips, tricks and insights to help you pass your registry!

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.